Should You Assist Migrants in the English Channel

At the time of writing this (Nov 2021) more than 25,700 migrants have attempted to cross the English Channel to the UK, in small boats, this year. Last week at least 27 of these migrants drowned attempting the crossing. Everyday, Skippers with little more than an RYA Day Skipper certificate are confronted with this tricky situation.

Many of these crossings are being made in overloaded inflatable boats, some with engines, some without, almost none with toilets, food, and water. The RNLI is out almost every day rescuing exhausted, dehydrated, and hypothermic migrants from one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world. But what if you come across an overloaded inflatable at sea, should you assist? Or could you be accused of people smuggling?

We are going to answer some of the most pressing questions from yachtsmen about the migrant crisis and what action they should take.

Is This a New Problem?

In short, no.

Thousands of migrants attempt to cross the English Channel every year. The English Channel isn’t even the worst area for these dangerous crossings, data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees shows that at least 105,135 people have arrived in Europe via the Mediterranean so far this year.

The difference this year (2021) is that the number of migrants crossing the English Channel has tripled to an all-time high and the number of fatalities has multiplied by 7 times compared to 2020.

Migrants are entering British waters in higher numbers and the chances of British yachts coming across them is rising accordingly. The discussion about what to do when you come into contact has been ongoing for many years abroad, but now it’s a discussion we need to have in our own waters.

What Should I Do if I Come Across a Suspected Migrant Craft?

Migrant crafts are unlikely to pick up the radio and put out a distress call, they are trying to cross ‘under the radar’. However, this does not mean they are not in grave and imminent danger and they may need assistance. This is the first assessment we need to make.

Any small inflatable vessel out at sea should be a cause for alarm. It could be the liferaft from a yacht or small fishing vessel, it could have blown out from a beach with some unprepared bathers, or it could be a desperate attempt to cross to England from France. Regardless of who is on board, the persons involved are likely to be in trouble, and if life or vessel is in danger, it is our legal obligation to assist.

When assessing the situation, we should consider if they have sufficient food, water, shelter, and navigation equipment. Also, do they have a sufficient means of propulsion to reach safety and avoid shipping? If they don’t have all this, regardless of who they are, their lives are in danger and they need help.

This post from the RNLI gives some first-hand accounts of the conditions these migrants might be in: Statement on the humanitarian work of the RNLI in the English Channel.

‘Um, the most desperate situation I’ve come across was eight people on a small sailing catamaran, the kind you might have two people sail on a lake or river or close to the shore, and they were on this catamaran with no mast, no rudder and just some shovels to paddle it. And they’d paddled this thing about 80% of the way across the Channel and they’d been doing this all night. And they’d made it into the middle of the shipping lane, and they were just so exhausted they couldn’t go on and they had nothing left and they’d stopped. When we got there, they were so tired they hardly reacted to us being there. We approached them and showed them that we had water and we had food and asked them what they needed. They didn’t even have shoes. When we got there, as we approached them, they said don’t come any closer and they made me wait while they put their masks on because they were looking out for us.’

A quote from one RNLI crew member taken from the linked article above.

Having established that the suspect craft is indeed in danger, a skipper’s legal obligations are set out in the International Maritime Organization (IMO) Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) Convention Chapter V, Regulation 33.

‘The master of a ship at sea which is in a position to be able to provide assistance on receiving information from any source that persons are in distress at sea, is bound to proceed with all speed to their assistance if possible informing them or the search and rescue service that the ship is doing so. This obligation to provide assistance applies regardless of the nationality or status of such persons or the circumstances in which they are found. If the ship receiving the distress alert is unable or, in the special circumstances of the case, considers it unreasonable or unnecessary to proceed to their assistance, the master must enter in the log-book the reason for failing to proceed to the assistance of the persons in distress, taking into account the recommendation of the [International Maritime] Organization, to inform the appropriate search and rescue service accordingly.’

This clearly state’s that you have a legal obligation to provide assistance and should pay no attention to the nationality or legal status of those aboard. Your vessel might not be suitable to take aboard 30 migrants, but you may have space for the sickest, or for children. You might also be able to pass warm clothing, food, and water across, or launch your liferaft for them to use. Anything you can do to keep those persons alive until a suitable rescue craft with a larger capacity arrives.

Who Should You Inform

Of course, if you suspect they are migrants, regardless of their survival situation the coastguard should be informed immediately. Failure to do so could raise suspicions about you assisting illegal smuggling. Also, if any of the persons aboard show signs of ill health it would also be strongly recommended you contact the coastguard immediately for medical advice. But nothing relieves you of your obligations to help unless you have a good reason (e.g. it would risk your own life or vessel), which you must record in writing, and may later have to rely on to justify your actions.

Realistically, once informed, the coastguard will immediately take over the rescue operation and guide you on your next course of action, but remember, informing the coastguard does not relieve you of your responsibility to assist.

Isn’t This What the RNLI Are For?

The RNLI is a non-governmental organisation and has no legal responsibility to save lives at sea or assist in the migrant crisis. The RNLI’s lifeboats are mostly crewed by volunteers who will abandon their usual day to day activities at no notice and proceed to help vessels and persons at sea with all speed.

The coastguard will ask the RNLI to assist, but the RNLI are not obliged to and only do so out of compassion. We should be grateful for the service the RNLI voluntarily provides but never rely upon it.

What Happens Afterwards

If you do assist migrants in reaching the shore, they will be greeted by border force officials, provided with the necessary medical care and processed.

98% of those that reach the UK claim asylum. However, claiming asylum is a long process and can take months or even years, during which time the migrants will be housed in hostel-like accommodation and offered unpaid volunteer or charity work. They can also claim a cash allowance of £39.63/week whilst waiting for their asylum application.

As for yourself, you will likely be required to provide an account of events and left to carry on as you were. Depending on the scenario, you may have found it a traumatic experience. Post-traumatic stress disorder can cause difficulty in concentration and insomnia. If this doesn’t pass after a few weeks, you should contact your GP and seek professional help.

Summary

So long as it doesn’t obviously put you in danger, you should do your best to help anyone in distress, regardless of who they are. If you don’t, you could be prosecuted. If you choose not to, you should have a good reason and have it written in your logbook.

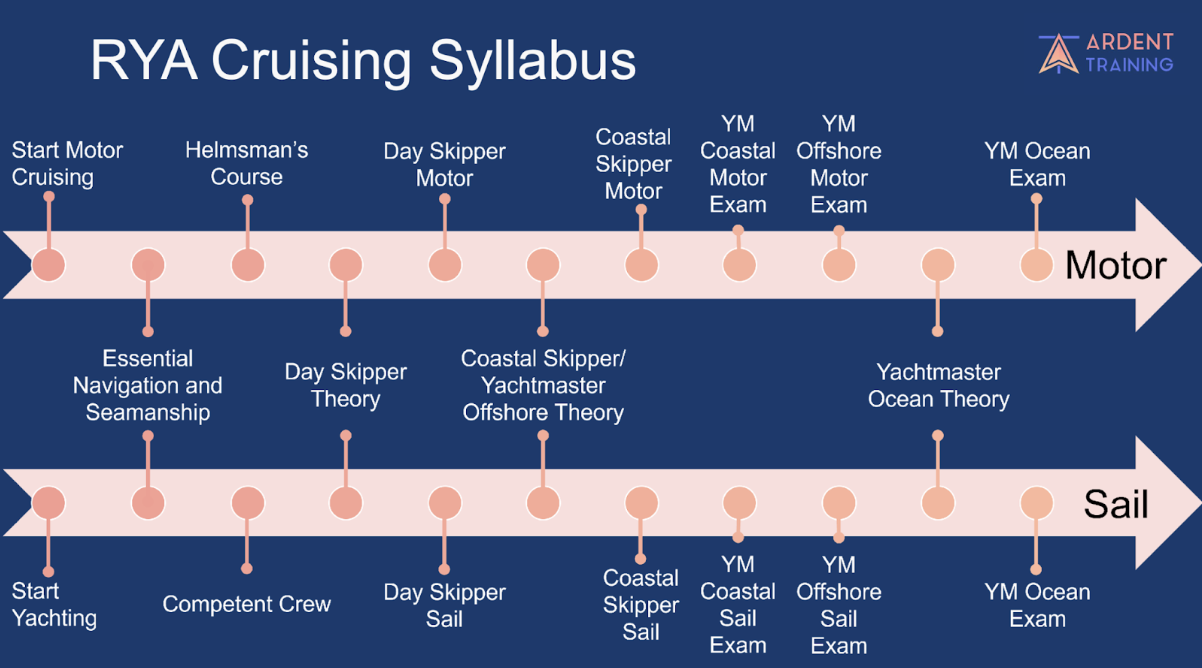

If you enjoyed this article, you should check out the FREE TRIAL of our online RYA Theory courses.